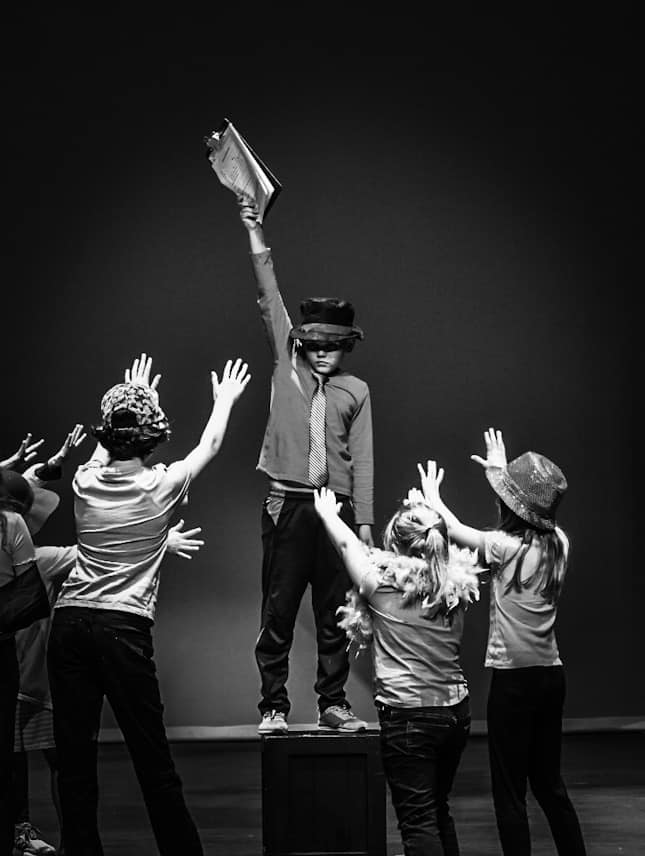

Rocket Kid was in a musical earlier this week as part of an extra-curricular semester-long theatre class he took through Childsplay. The performance included his class as well as all of the others in their “conservatory,” a total of seven performances.

One of the things I love about Childsplay is that the students and teachers collaboratively create, hone, and perform original scripts. We got to witness seven world premiers that night.

Most of the kids knew most of their lines, and in two hours of performances only two or three times was someone standing on stage, wondering what they were supposed to be saying. While the performance quality varied by child and by class, overall, they did a nice job, and all of the shows were entertaining.

The director of the organization spoke before the performance started, explaining to the audience that making mistakes in their classes is celebrated. While I’m sure there’s an upper limit on that, if you want to elicit creativity, mistakes have to be safe.

You can’t have creativity without vulnerability, and you can’t have vulnerability where mistakes are penalized.

From brainstorming storyline ideas to trying out character personalities to any and every gesture and voice inflection, the performers are taking risks and putting themselves out there at every rehearsal, and then again during the performance.

Many of us only consider the “remember your lines” aspect of being on stage in this context, but how did they choose to dress? What do they look like when they’re not delivering lines? What do they look like when they are delivering lines? Do they know the choreography? Do they know the songs? Not just the words, but the pitches and the rhythm? (How many adults have done karaoke only to realize that they need more than just the words to be able to sing the song?)

The vulnerability is not limited to children, to community theatre, to acting. We all have opinions about anyone we’ve ever seen perform: plays, musicals, musicians, comedians, authors, dancers, and more. The venue doesn’t matter. A formal performance space establishes a different buy-in and mindset for an audience than a street performer, for example, but the thread of “I’m going to offer my interpretation of this thing for your consumption and I hope you like it” runs throughout.

Do we want to go see someone perform who doesn’t care at all if the audience likes it?

There will always be someone who doesn’t like it—nothing is for everyone—but does the audience as a whole like it? Did people clap enthusiastically or politely? Did people come to the second show? Did people buy a CD or a T-shirt or tell their friends?

Sure we do it because we love it, and that doesn’t eliminate the vulnerability or fear of falling flat, whether because we make mistakes in the delivery or because the content wasn’t what the audience was looking for.

In the realm of kids—be kind. On the whole, kids have good bullshit radar, so if there was an obvious train wreck, don’t pretend you didn’t notice it. But complimenting their hard work and/or the parts that went well goes a long way. The more specific you can be with compliments, the better. (That is always true, not just for theatre, and not just for kids.) “I loved when you jumped up on the box with the clipboard” is more meaningful than “The first song was really good” is more meaningful than “I loved the whole thing.”

We tend to discount their feelings—nervous, excited, anxious, exhilarated, devastated—when in reality, most of us would not be brave enough to do what we just watched them do. Honor their risks and acknowledge all the feelings.

For the not-kids—give some empathy and emotional and/or financial support to the performers you love. (Spotify isn’t paying them.) Send a letter or an email or a tweet complimenting something they’ve recently published or something you’ve enjoyed repeatedly. Buy the record or the T-shirt or the concert tickets (not from resellers, if at all possible) or back the Kickstarter.