I have had so many conversations with colleagues near and far recently, and there have been two themes with regards to deficiencies in many of our students (though I wish I could say the problem was limited to just students…).

One is attention to detail.

How do you teach attention to detail?

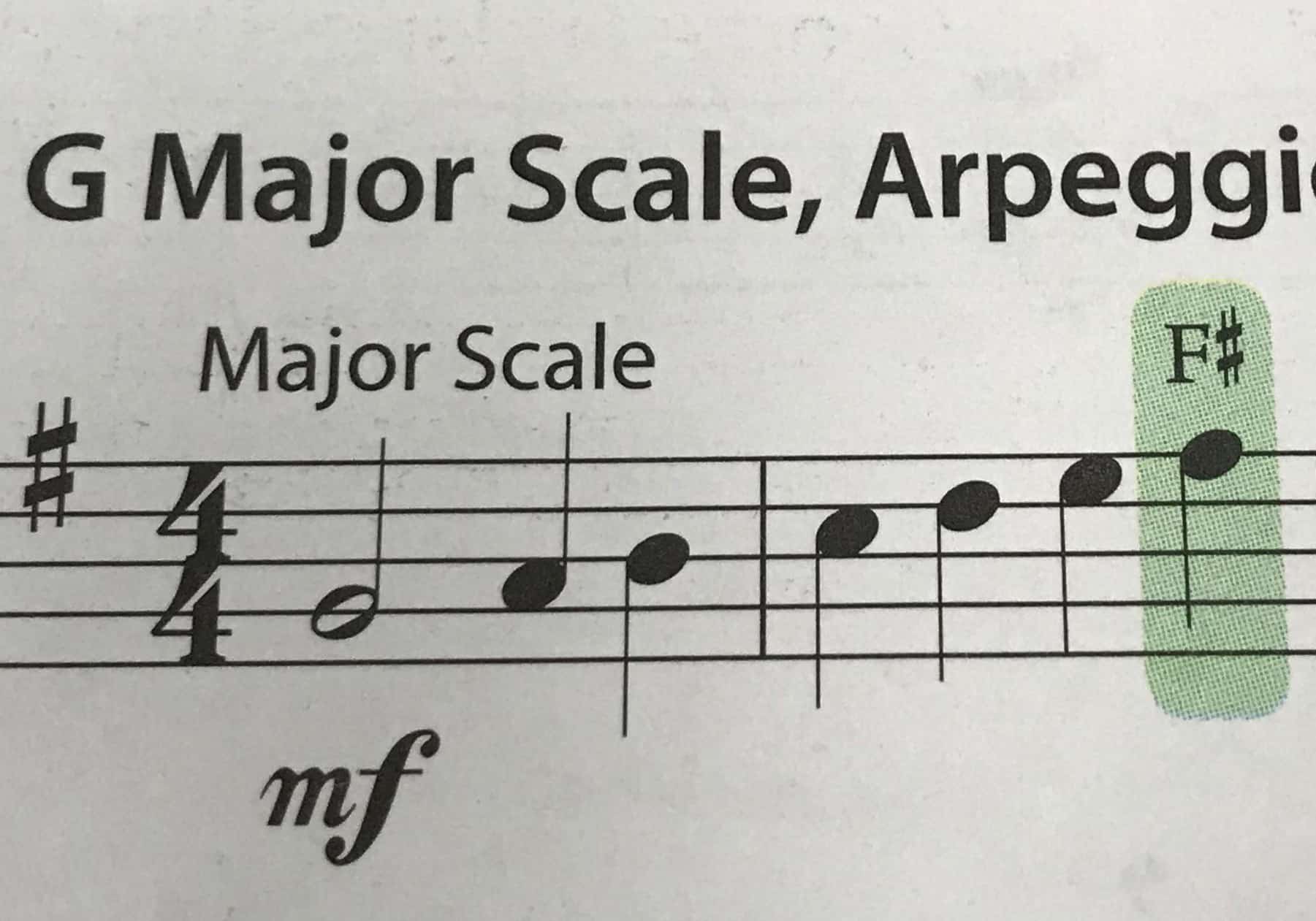

A student in a colleague’s band had a playing test on the G Major scale. The student had music as pictured to work from. Despite the highlight and label, the student didn’t play the F#.

I gave a written test to my classes years ago when I was student teaching. The extra credit question was “Spell quarter note.” A significant number of kids got it wrong. Wrong! (They left out the second R, which is how they were spelling it previously.)

There are endless examples of simply not noticing details. And yes, we all do it in some way or another some of the time, but ’round here, it’s chronic.

I think much of it ties in to the second theme.

I can’t teach people to give a shit.

Let’s say, in the above example, the kid saw it but played it wrong because he didn’t care. “I got most of the notes right,” or “Band isn’t important anyway,” or “I’m not going to play next year so who cares what I do now?” How do you change that?

Most often, we use punitive measures—we’ll lecture you or lower your grade or call your parents or revoke a privilege. Parents do the same—we’ll revoke a privilege or yell at you or hit you. They work OK sometimes, but if they gain us anything, it’s only compliance, not investment. And there is almost always a next time.

I teach a subject that kids have to opt into. Parents need to take steps to acquire instruments for their kids, even if it’s a school instrument. And still, there are so many of them who just refuse to engage, regardless of what the project is for that day.

I understand that sometimes, kids (all people, actually) act like they don’t care when they do, as a means of protection. “I can’t do this (or I’m afraid I won’t be able to do this) so I’m going to act like it doesn’t matter and I’m choosing it to be that way. This way, I feel like I’m in control and I don’t need to be vulnerable.”

I also understand that just teaching kids to be compliant is not ideal. We need kids to be active and engaged and thinking and experimenting and learning the way that kids—all people, actually—learn best. There is high value in rule-breaking in some contexts, but it’s not typically willy-nilly “I don’t feel like doing that” that’s valuable, in or out of school.

All that said, there is a requirement for some degree of compliance in any social space. There are boundaries (rules, procedures) and, for the most part, they have good cause. We can have roads and freeways and grocery stores and malls and parks and movie theatres and on and on because of these boundaries—and we get angry (and potentially hurt or killed) when people in those spaces disregard people around them.

My classroom has rules and procedures, and I work to adjust the space for students who need it, or for students who make a reasonable and implement-able request.

Not everyone is interested in all things. Not everyone who is interested is interested to the same degree. I fully understand all of that (and certainly see how it applies to all people, not just my students). But if you’re going to have to be here, you might as well try to get something out of it.

It used to be that I’d consistently have kids in band who didn’t do well in the rest of school but loved playing their instrument. They behaved better for me. They worked harder for me. My class was where they thrived.

I don’t have that any more, or I haven’t in the last few years. I feel like the kids who might have been those kids are already checked out and won’t even try. Even with explicit invitations, those kids are gone.

I have spent a lot of time this school year talking to kids about emotional safety. About how mistakes are normal and OK and we all make them, including me. About how we need to make the space safe for each other, that that’s not something I can do by myself. About how, as a team, we’ll be better if each one within the group has space to learn and to mess up and to grow. Because we can’t learn this skill without messing up. You’ll make mistakes on your instrument for as long as you play it.

Maybe there are kids I’ve reached, kids who have received this message and changed their behavior somewhat. Or their perspective. Maybe they were already safe for other people but now feel other people are a little bit safer for them.

I don’t know. I’ll probably never know. (This is one of the things about teaching. Planting seeds that you often never see sprout, much less thrive. Shout out to former students who have gotten in touch.)

I’m at a loss. I don’t know how to teach attention to detail. I don’t know how to teach giving a shit (to students; sometimes also to parents; occasionally to colleagues). Not only does the success of my classes require it, but the success of our businesses, of our economy, of our families, of our country all require it.

0 thoughts on “How do you teach…”